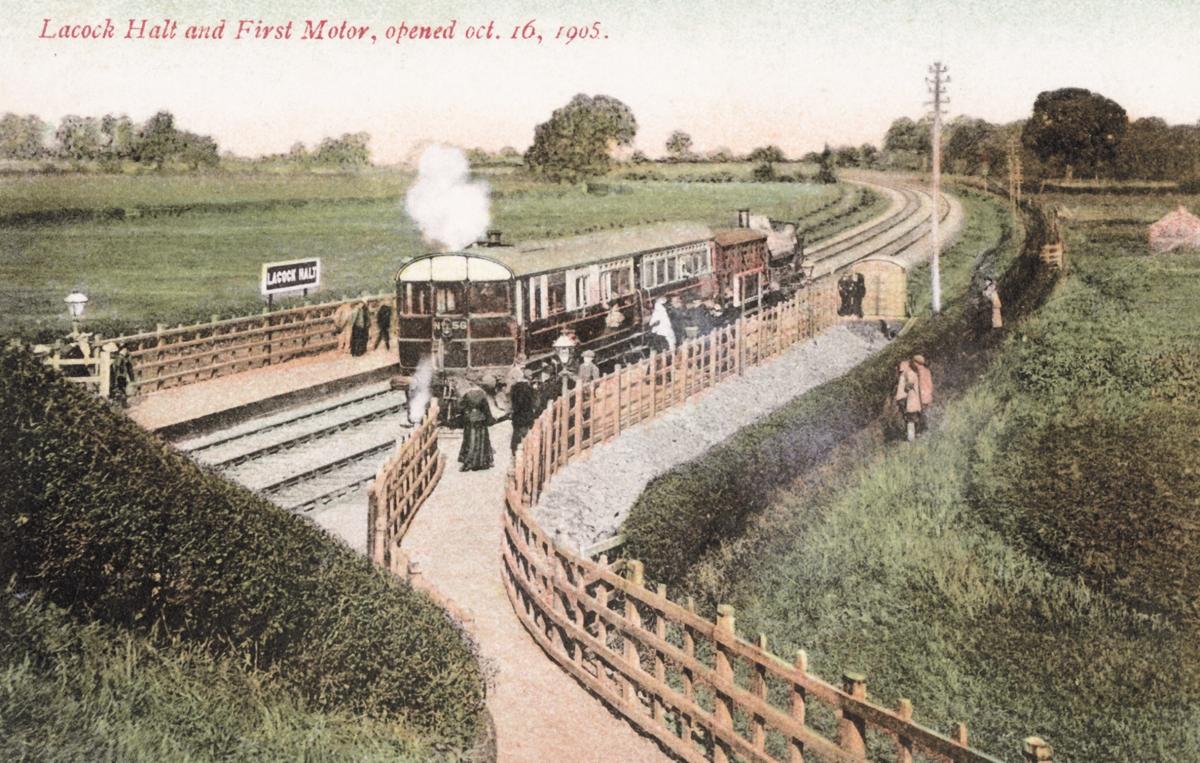

IT was an age when you could take a train from Lacock to Weymouth for a holiday by the sea and when fresh milk was delivered to the front door by the churn.

Chris Breach’s book Lacock From Old Photographs is a sepia filled delight taking in aspects of the village before the modern age of colour photos and television.

The photographs are largely from the late 19th century through to the Second World War with most depicting the era of Edwardian England when photography had become the norm.

From the High Street to West Street, and from Bewley Common to Lacock Abbey where photography was born with the pioneer and inventor William Fox Talbot, the book covers not just the buildings but the people.

Take for instance the on page 83 the picture of three farm workers trying to get a reluctant calf into the back of a trailer. Taken by Harold White in the 1940s the photo was commissioned by the British Council for a book about how British people work and live as part of the propaganda to boost morale. It’s an image that reflects the adhoc nature of rural live anywhere and is both charming and comic at the same time.

In complete contrast to the undignified attempt to transport the calf is a phone two women in a decorated pony and trap taken in 1902. Beautifully dressed the duo appear to have cast a spell over their pony as it stands stock still without a trace of embarrassment with flowers and ribbons adorning its head and body. Again, it is both charming and mildly comic.

On a more sombre note a photograph on a War Memorial dedication service taking place in 1920 St Anne’s on Bowden Hill is an interesting flashback into the event. A large group of people stand in a semi-circle following the Rev Mereweather’s words by the newly erected Celtic cross to mark the fallen of a war that had only ended a few months earlier. The men have removed their hats in deference while the women keep their hats on. No poppies in evidence or lines of ex-service personnel on the August day. Instead it’s the quiet but casual dignity of those present that captures the attention as the village lost ten of its men to a conflict still fresh in the mind.

The chaps in the photo of a 1940s card game in the Working Men’s Club at Cantax Hill is one of the delights of the book reminding the reader that at the turn of the 19th century and well into the 20th the village would have held a strong working class element with agriculture a big employer. There would have been shops and services that have long since gone – a pity – although it has a new life in an age when its ancient streets and buildings feature as backdrop to films and television shows.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here